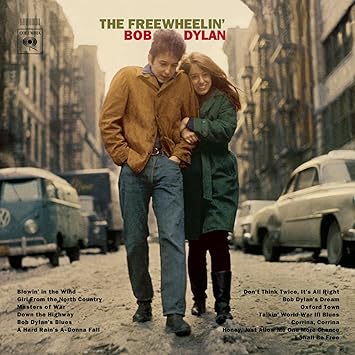

On the cover of Freewheelin‘ both Suze and Bob look a little chilled. Suze is curled up next to him leaving no space in between and Bob’s got his hands in his pants pockets. He also has the buttons up top buttoned, the bottom two are opened, and if you look close you can see a lilt to Suze’s hair, the wind seems to be blowing towards them, not behind, on this two way New York Street.

Suze is looking at the camera; Bob’s eyes are directed at the ground, looking for that “restless piece of paper . . . that’s got to come down some time . . .”?

Bob also said that you got to feel it in the wind, this elusive answer, that is forever blowing, or forever just beyond our grasp or evading our sights.

What we can see or hear are the terrific rhymes; the pattern is consistent, and it keeps the song easy to hear and pleasing to the ears. The rhyme scheme is a/b/c/b/d/b/d/d. Easy as a, b,c.

What may not be so easy to see, though we do hear them are the internal rhymes. There’s one in each verse. In verse 1, “seas” rhymes in the middle of the next line with “sleeps.” In the second, “how” with “allowed,” and for a thematic punch in the third, “ears” with “hear.”

Let’s stick with that last one a bit. There are only two things that can be heard in this song–the cannonballs flying in verse 1 and the people crying in the last verse. Oh, and a third, the wind, you can hear the wind blowing, and you can hear Dylan, singing above it, singing into it, breathing life into a song that is a beloved anthem to the power of questions for protest.

Here’s a less than a minute clip from the concert for Bangladesh, 1971:

And here’s a live performance of the whole song on TV in 1963:

How many roads must a man walk down

Before you call him a man?

Yes, ’n’ how many seas must a white dove sail

Before she sleeps in the sand?

Yes, ’n’ how many times must the cannonballs fly

Before they’re forever banned?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind

How many years can a mountain exist

Before it’s washed to the sea?

Yes, ’n’ how many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

Yes, ’n’ how many times can a man turn his head

Pretending he just doesn’t see?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind

How many times must a man look up

Before he can see the sky?

Yes, ’n’ how many ears must one man have

Before he can hear people cry?

Yes, ’n’ how many deaths will it take till he knows

That too many people have died?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind